Socioeconomic Status and Health

A study we conducted in Alameda County, California, demonstrated a difference in survival over an 18-year period for people with various levels of family income. 18 As shown in Figure 1, improved survival was associated with higher socioeconomic position. Those who had higher incomes at the beginning of the study survived better. At the end of the 18-year period, the death rate for persons with inadequate income was twice that for those with adequate income. Data for the United States show similar results. For example, in one analysis of a sample of 340,000 deaths in 1960,16 it was found that in every age group white men with incomes below $2,000 had mortality rates approximately 50 percent higher than all other men.

The prevalence of specific diseases among lower socioeconomic groups is also higher. 19 For example, in 1972 people with incomes less than $3,000 had three times the rate of heart disease as those with incomes greater than $15,000. The burden of diabetes was almost 3.5 times greater in the poorest group. Similarly, rates of anemia and arthritis were 2.5 times higher for the poor.

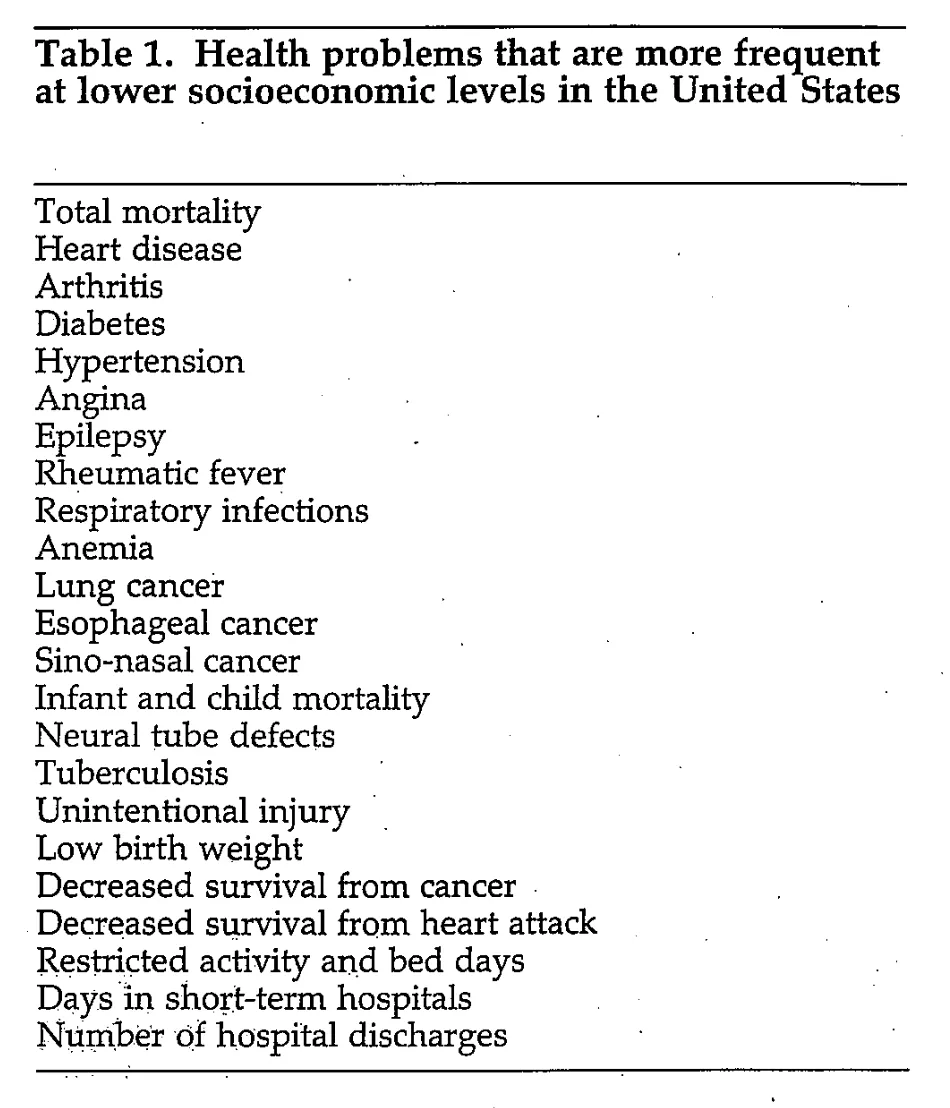

Table 1 lists other health problems that are more severe in the lower socioeconomic levels. The most obvious explanations are inadequate medical care, low income, poor nutrition, unemployment, race, and hazardous living circumstances. However, these possible explanations are inadequate for two reasons. First, although it is true that higher rates of morbidity and mortality occur among those in the lowest socioeconomic group, high rates are not exclusive to that group. Instead, a gradation of rates is often seen, increasing from the highest socioeconomic level to the lowest. It is difficult to argue that those at level 2 or 3 have inadequate medical care or nutrition or that they live in hazardous circumstances, and yet those at levels 2 and 3 have higher rates of disease than those at levels 1 and 2, respectively. The issue posed by the observation of higher disease rates relative to socioeconomic position is not simply that of position based on the subject's amount of money or of poverty compared with near-poverty or affluence, but of other factors as well.

[...]

This conceptualization, which combines demands and resources, may help to explain why not all persons of low socioeconomic position become ill. For example, a person living in a high crime area on a fixed income may have better health if she or he has friends and neighbors on whom to rely for help than another person who lives in the same circumstances but has fewer social connections.

Furthermore, the balance between demands and resources changes as one moves up the socioeconomic ladder. Although demands may increase, resources increase even faster. Such a view of socioeconomic position is important because it suggests that changes in demands and resources may help to alleviate the burden of illness associated with lower socioeconomic status.

[...]

Finally, in poor neighborhoods, intervention efforts that have focused on demands and resources appear to be associated with improved health among residents. A program now under way in the Tenderloin area of San Francisco is aimed at increasing social ties among isolated, elderly, and poor residents of this area. Reductions in neighborhood crime and improved food access have already been accomplished, and there are some indications of improved health. Bringing residents of these areas together to work on common problems has allowed them to develop social resources that have reduced some of the environmental demands in these locations. These heightened social resources in combination with system resources such as Meals on Wheels, home health aides, and other services show real promise in improving the health of residents in these areas.

George A. Kaplan, Ph.D. et. al, Socioeconomic Status and Health - University of Michigan library 2024, WEB 2024