The rise and decline of the American ghetto (case study)

The "ghetto phenomenon" and its roots.

Knowledge BaseThere is a similar trend towards disinvestment by the business community at the neighbourhood level and a reorientation to larger and regional markets in the US. The structural changes in retailing and the consequences for residents of urban neighbourhoods have been examined in a number of studies (for example, Bingham and Zhang, 1997). The loss of neighbourhood businesses has been more pronounced in low-income and minority ethnic communities in the central cities and inner suburbs. In many cases, the lower levels of competition have led to unfair pricing schemes that take advantage of the captive market. In other cases, gaps in key retail and service sectors, such as supermarkets and banks, have emerged leaving residents with the choice of travelling out of their neighbourhood to obtain items for their household, purchasing them at higher costs at convenience stores, or doing without (Troutt, 1993; Cotterill and Franklin, 1995). Several US studies have documented the failures of the food retailers to meet the needs of residents in poor communities (Ashman et al, 1993; Sustainable Food Centre, 1995; Gottlieb et al, 1996). In the past 30 years, the supermarket industry has become increasingly more centralised; the total number of food stores has declined while at the same time the average store size has increased steadily (Public Voice for Food and Health Policy, 1995 and 1996). The movement of supermarkets to suburban locations paralleled trends in population shifts and new transportation corridors (Yim, 1993) and thus, larger chain grocery stores are disproportionately located in the suburbs than non-chain stores (Chung and Myers, 1999). The existing stores in urban areas located in or adjacent to poor neighbourhoods were closed or sold and the combined effect has been to create an urban grocery store gap as low-income areas have fewer and smaller stores per capita (Cotterill and Franklin, 1995).

Meanwhile, public transport services have largely failed to adapt to new land-use and activity patterns on both sides of the Atlantic. This may explain why the car accounts for the vast majority of the travel of all income groups (see Figure 2.3). High car dependency, even among the lowest-income households, suggests that public transport is generally inadequate to the mobility and accessibility requirements of a modern society and that even those on a low income will go out of their way to own or gain access to a car. People without cars usually take more time, expend greater effort, and pay a higher marginal costs to reach the same destinations as people with cars (see Figures 2.3 and 2.4). This may explain the shorter distances they travel and would suggest they are less able to access the full range of services and amenities available to car drivers. In the US, there is an increase in the average journey distance with increasing income but this is less marked than in the UK; the average journey time hovers around 20 minutes for all income groups. The longer journey times for shorter distances is explained in part by their greater reliance on slower modes of travel such as transit and walking.

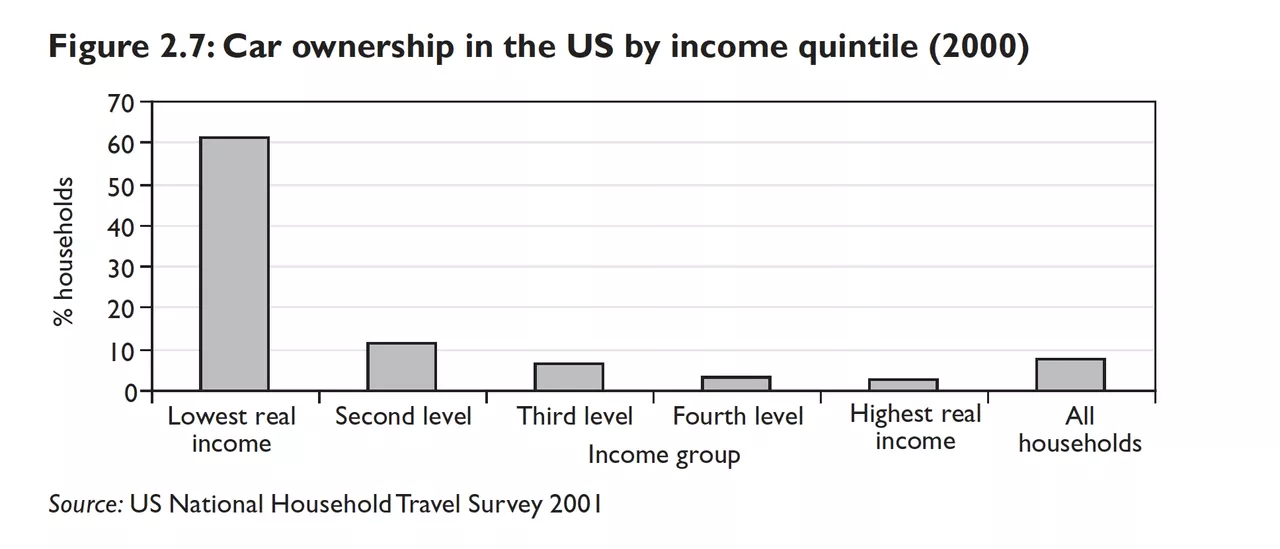

In 2001, 61% of households in the lowest income category in the US did not have access to a vehicle. This would suggest that, in most instances, non-car ownership is usually not a choice but rather based upon affordability and/or an inability to drive.

Since non-drivers and people without regular access to a car tend to be concentrated among households in the lowest-income groups and in the mostdeprived neighbourhoods, they are already at risk of social exclusion. Women, lone parents, older people, people with disabilities, people from minority ethnic groups and young people are all less likely to live in households with a car. However, the people who are solely dependent on walking, cycling and public transport or mass transit services have not traditionally featured as significant factors in the development and implementation of mainstream transport policies (Bruton, 1993). Ironically, these are the very people that are more likely to need to use key public services, such as healthcare facilities, schools, colleges and welfare services.

In a highly mobile society, a lack of adequate transport provision means that individuals become cut off from employment, education and training and other opportunities. This in turn perpetuates their inability to secure a living wage and thus to fully participate in society. Poor access to healthy affordable food, primary and secondary healthcare and social services exacerbates the health inequalities that are already evident among low-income groups, further reducing their life chances. People can become housebound, isolated and cut off from friends, family and other social networks. This can seriously undermine their quality of life and, in extreme circumstances, may lead to social alienation, disengagement and, thus, undermine social cohesion. Poor transport links and polluted and unsafe walking and waiting environments reduce social and economic activity within deprived communities. There can be knock-on effects in terms of crime and anti-social behaviour, with implications for personal safety and the more general desirability of these areas. Businesses suffer from the loss of custom and this encourages the flight of services from these areas and a reduced local employment base. Poor accessibility into and out of many deprived areas also discourages inward investment and leaves them abandoned and isolated. In turn, this costs the state in terms of higher welfare payments and reduced tax contributions. It also serves to undermine the wider social policy agenda in terms of reducing unemployment, improving educational attainment and reducing health inequalities. The evidence for this is stark, although it remains underresearched and poorly examined by the welfare professionals charged with the task of addressing these social ills.

The "ghetto phenomenon" and its roots.

Knowledge BaseHow segregation causes poverty

Knowledge Base