Sociological Theory - Emile Durkheim

Social Facts

Durkheim developed a distinctive conception of the subject matter of sociology and then tested it in an empirical study. In The Rules of Sociological Method ([1895] 1982), Durkheim argued that it is the special task of sociology to study what he called social facts (Nielsen, 2005, 2007a). He conceived of social facts as forces (Takla and Pope, 1985) and structures that are external to, and coercive of, the individual. The study of these large-scale structures and forces—for example, institutionalized law and shared moral beliefs—and their impact on people became the concern of many later sociological theorists (Parsons, for example). In Suicide ([1897] 1951), Durkheim reasoned that if he could link such an individual behavior as suicide to social causes (social facts), he would have made a persuasive case for the importance of the discipline of sociology. His basic argument was that it was the nature of, and changes in, social facts that led to differences in suicide rates. For example, a war or an economic depression would create a collective mood of depression that would in turn lead to increases in suicide rates.

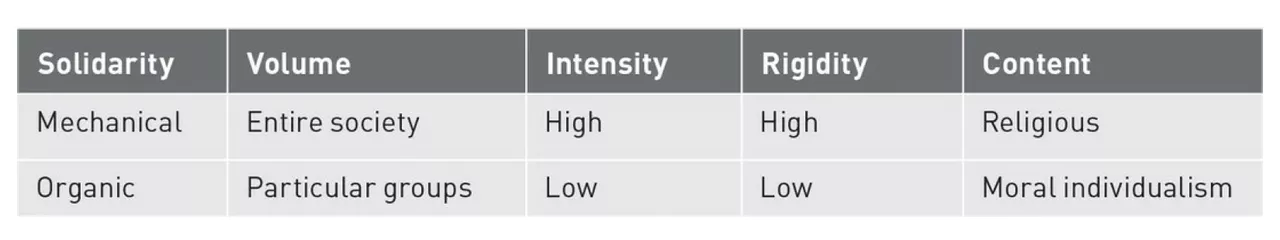

In The Rules of Sociological Method ([1895] 1982), Durkheim differentiated between two types of social facts— material and nonmaterial. Although he dealt with both in the course of his work, his main focus was on nonmaterial social facts (for example, culture and social institutions) rather than material social facts (for example, bureaucracy and law). This concern for nonmaterial social facts was already clear in his earliest major work, The Division of Labor in Society ([1893] 1964). His focus there was a comparative analysis of what held society together in the primitive and modern cases. He concluded that earlier societies were held together primarily by nonmaterial social facts, specifically, a strongly held common morality, or what he called a strong collective conscience. However, because of the complexities of modern society, there had been a decline in the strength of the collective conscience. The primary bond in the modern world was an intricate division of labor, which tied people to others in dependency relationships.

Dynamic Density

The division of labor was a material social fact to Durkheim because it is a pattern of interactions in the social world. As indicated above, social facts must be explained by other social facts. Durkheim believed that the cause of the transition from mechanical to organic solidarity was dynamic density. This concept refers to the number of people in a society and the amount of interaction that occurs between them. More people means an increase in the competition for scarce resources, and more interaction means a more intense struggle for survival between the basically similar components of society.

The problems associated with dynamic density usually are resolved through differentiation and, ultimately, the emergence of new forms of social organization. The rise of the division of labor allows people to complement, rather than conflict with, one another. Furthermore, the increased division of labor makes for greater efficiency, with the result that resources increase, making the competition over them more peaceful. This points to one final difference between mechanical and organic solidarity. In societies with organic solidarity, less competition and more differentiation allow people to cooperate more and to all be supported by the same resource base. Therefore, difference allows for even closer bonds between people than does similarity. Thus, in a society characterized by organic solidarity, there are both more solidarity and more individuality than there are in a society characterized by mechanical solidarity (Rueschemeyer,1994). Individuality, then, is not the opposite of close social bonds but a requirement for them (Muller, 1994).